|

| By BEN HUGHES

From the 1971 book entitled, "Cenrury of Adventure". WHEN YOU DRIVE over the Big Qualicum concrete bridge, 106 miles north of Victoria on the Island Highway, the scene is peaceful enough. But you are within bow-shot of one of the most chilling massacres in the blood-stained annals of Indian tribal warfare on the Pacific coast. A handful of white men camped less than a mile away watched the raiders come anal go and were at the scene of the tragedy a few hours after the slaughter occurred. The story is told by the historian of early days in B.C., Dr. W. W. Walkem, after a talk he had with Adam Horne, chief factor for many years for the Hudson's Bay Company at Nanaimo. In May, 1856, when he was a young man of 25, Adam Horne was selected by Chief Factor Finlayson of Fort Victoria to find a trail across Vancouver Island to the west coast. The factor told the young Scotsman that it was a dangerous mission; the natives were not well-known to the company but their relatives at Cape Mudge, the Euclataws, had a very bad reputation for treachery and theft. If the Qualicums refused to give him any information, he was to leave their camp at once and use his own discretion in completing the assignment. The party was selected with great care, the factor appointing a French-Canadian named Cote as the guide because he was a good canoe man, knew the waters of the coast thoroughly and didn't know fear. The interpreter was also selected by Finlayson. The young Scotsman noted that he had a great but profane flow of language, but as it was always in French, it didn't shock him too much. One of the four men Horne was allowed to choose was an Iroquois, an old "engage" of the company. |

|

|

| The little party left Hudson's Bay Company's wharf at the foot of Fort Street before dawn in a Haida-style canoe, roomy and light and rising like a duck on the whitecaps outside.

On their way north the party called at Salt Spring Island and passed a large number of Cowichan Indians, fishing. They ran on a mud flat five miles south of their objective but soon got off again. They now lit no fires and took every precaution to keep concealed as they believed they were in hostile country. From a sound sleep in a snug cove protected from the Qualicum or west wind, which was blowing hard, Horne was awakened by the Iroquois with a finger on his lips. He said he had been scouting around and they were within one mile of the. Qualicum and he had been watching for some time a large fleet of northern canoes approaching the creek mouth. From the edge of the timber in which they were hidden, the white men watched the canoes enter the creek one after the other and disappear. While they were breakfasting they saw thick columns of smoke arise from the creek and pour into the timber in which they were concealed. They lay from 7 'til noon before they saw the first of the canoes come out of the creek. The Haidas in their great war canoes were war-whooping in triumph, one or two of them standing upright and holding a human head in his hands by the hair. |

|

| The wind was blowing a near hurricane from the north but the Haidas hoisted mats for sails and were soon flying before the gale.

In four hours they were all out of sight. The little party of watchers allowed another hour to go, then struck camp and poled their way along the shallow beach 'til they came to the mouth of the Qualicum, which they entered from the north. Very cautiously they worked their way up the river against a swift current. Bush cut off their view and they proceeded very cautiously with their loaded muskets at their sides ready for instant use. They had seen nothing yet of the Qualicum rancherie but volumes of smoke were pouring still from one side of the stream. Shortly they rounded a bend and were stricken dumb at the scene! The rancherie was a heap of blackened timber, still burning. Naked bodies could be seen here and there lying in the clearing surrounding the rancherie. There was no sign of any life. The interpreter called out that they were friends and there was nothing to fear; but there was no answer. Then very cautiously, they walked over to the bodies to find to their horror that they were all headless and fearfully mutilated. They searched everywhere for a living human but without success. |

|

| While they were discussing the problem the Iroquois suddenly left them and walked diagonally towards the bank of the creek. Then he halted, with his head cocked to one side, like a robin listening for a worm in the lawn.

He stood like that for several moments and then, in his moccasins, glided towards the creek. There he lay down with his ear to the ground. Rising at length, he went a few yards farther down the creek and lay down again with his ear over the edge of the bank beneath an overhanging maple tree. Extending his arm he bent it under the bank and drew out the naked body of an Indian woman. She was a fearful sight, old and wizened, but still clutching a bow in her dying grasp. She was chanting a dirge in a low monotone and it was this the Iroquois had heard. She had a spear wound deep in her side from which blood was pouring. Her face was bloodless and she was too weak to offer any resistance but after many attempts, in gasps, and between long pauses she told the elf-locked interpreter the story. They had all been asleep when the Haidas poured in from the river after beaching their canoes soundlessly, and more than half of the little tribe were killed before they were awake. They were lucky. The others were cruelly killed because there were five Haidas to every Qualicum. She was wounded by a spear but she had seized a bow and fled to the creek where she hid beneath the bank under the roots of the giant maple. She said that after killing all the grown men and women the Haidas had taken away with them as slaves two young women, four little girls and two small boys. She whispered that the Haidas had massacred the. tribe because one of the northern warriors had been killed at Cape Mudge when he had tried to carry off the daughter of one of the Euclataw chiefs. The Euclataws were too strong for the Haidas but the Qualicums were a Euclataw sept and the Haidas took their revenge on them. Gradually her voice became weaker and weaker, her breathing more labored and finally she became insensible, and even as Horne looked at her, her eyes became fixed, her jaw dropped and she died ... |

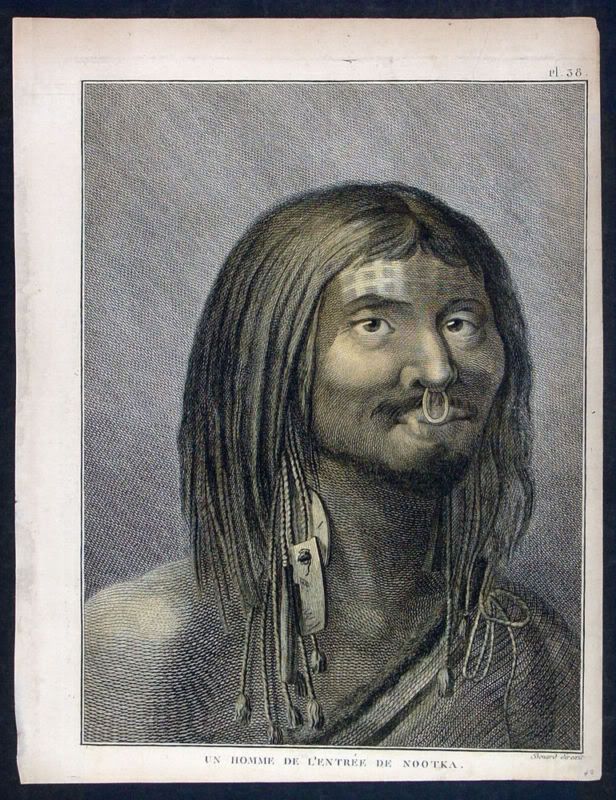

| Life was very tough for the early First Nations & Native warfare was even tougher... |

HOME

HOME

|